Today's post will be a quick one; I am hoping that you all save your word-count quota for the subsequent entries this post details. I have been at work on a few different write-ups, and I decided to turn them into a recurring series on The Development Section:

Under-Appreciated Composers for Eager Appreciators

The list of composers held in the pantheon of undisputed greatness is already long and unwieldy. Since these composers are all considered vital for understanding the evolution of classical music, it becomes difficult to devote the time needed to take a musical road less-traveled. Unless the performer or label is well-known, it can be risky to record music outside the "greatest hits" of the standard repertoire, making some genuinely great music all the more difficult to come by. New listeners are sometimes discouraged from listening to obscure composers without first gaining context by listening to the works of "pantheon" composers, and so the cycle begins anew.

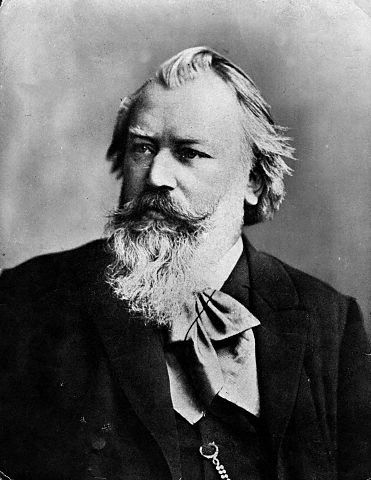

For this reason, I have decided to start a small series of write-ups on some composers who, in my personal opinion, merit closer attention, even if that closer attention only takes the form of forty minutes spent with a long-forgotten string quartet and a glass of wine. The write-ups themselves will not be much: simple biographies, sometimes with the benefit of historical context, a small selected bibliography, and perhaps a portrait of the composer if there is one in the public domain. More importantly, I will try to embed high-quality performances of selected works when possible, and when not, I will provide "For Listening" and "For Further Reading" lists. If even one person seeks out a few works by one of these composers, then this little blog will have done more than I could reasonably expect of it.

In general, there are some common threads that have hurt certain composers' legacies, keeping them away from the tips of listeners' tongues:

1. The composer wrote in a conservative style. By my count, two composers sit on the "pantheon," without debate, who spent their careers perfecting what came before rather than introducing something new. Granted, they are regarded as two of the very greatest:

|

| Wikimedia Commons. |

|

| Wikimedia Commons. |

For most composers, innovation had a large part to do with legacy. Conservatives often ended up enjoying local and regional success in their lifetimes, but as History selected some other composer to be the one most "characteristic" of their styles, they were left on the library shelves to be forgotten.

2. Frankly, the composer is not quite "great." This affects many composers from the first list. Perhaps Bach, Mozart, and Brahms never composed any weak music, but basically every other composer has at least one "dud" to his or her name. This is the nature of creation: those who are unafraid to fail while exploring the union of personal expression and human aesthetics are those who can achieve greatness. However, odd decisions and uncontrolled changes are the rule rather than the exception for some composers. Often, this leads to the reasonable conclusion that these composers were weak writers, but that conclusion runs the risk of marginalizing some wonderful works that are just as capable of elevating the human spirit as works by the glorified masters. Think of all the one-hit wonders on the radio. Some of those "one hits" can move you to tears, make you drop everything and dance, or get an entire room singing along, without irony, faces lit up with joy. Do we ignore those hits just because their authors lack a catalog of eight multi-platinum, Grammy-nominated albums?

3. The composer was born in the wrong place or time. Personal liberty has come a long way in the last several centuries. It is unthinkable now that any musician would be censored or controlled unless his or her music literally incited riots and crimes. However, many composers have not enjoyed this same sense of freedom, often due to ethnic or religious background. Thus, some composers have lost their seat at the "pantheon" just for being born the wrong way.

4. The composer is female. Music history is sexist. Exactly one opera by a female composer has been produced at the Met. This is actually scheduled to change in the 2016-17 season, but over a century will have elapsed between opera by female composers. Over a century has not elapsed between great female composers. I, for one, am tired of the "classical music is dying" tropes, but rather than go after perceived stodginess in the music, if I were trying to make that argument, I would start with the culture of sexism that continues to shape the course of classical music history.

With all of this having been laid out, I have about six composers I am interested in introducing through this blog series, but I am hoping to receive some requests. I am happy to do a little research if needed, and if my listeners' digests are any good, perhaps your suggestion will have helped somebody else find a way into classical music. -SB

Written Reflections

- What composers would you like to see featured in a series of this title?

- Do you often seek out less-appreciated music, classical or otherwise, or do you prefer to have these works "come to you" in the form of curated lists and personal recommendations?